June 12, 2017

Sarah Giffin

Senior Program Associate

Senior Program Associate

There we were- educators from libraries, after-school programs, school classrooms, and community-based nonprofits– in the Chattanooga Public Library’s makerspace, pouring over books on the city’s history. These weren’t books you could get on Amazon. They were locally published by local authors, written from the research materials found in family attics and photo albums. We were on a ghost hunt, and the past seemed to be colliding with the present day each page we turned.

~

Let’s back up. Global Kids was invited to Chattanooga through the Mozilla Gigabit Community Fund to train local educators in a Global Kids designed curriculum where students investigate local history and create a socially conscious, geo-locative game related to their historical content. (Think Pokemon GO, but the Pokemon are historical figures and you are a social justice time traveler.)

~

Let’s back up. Global Kids was invited to Chattanooga through the Mozilla Gigabit Community Fund to train local educators in a Global Kids designed curriculum where students investigate local history and create a socially conscious, geo-locative game related to their historical content. (Think Pokemon GO, but the Pokemon are historical figures and you are a social justice time traveler.)

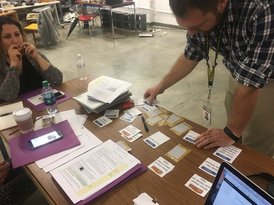

Participants create a paper prototype of their game world.

Participants create a paper prototype of their game world.

Haunts was created to be student interest driven, but this professional development (PD) training demonstrated the importance of giving educators time to explore a program as a participant before bringing it to students. Through a personalized and collaborative learning process educators are able to uncover the link between the social ails of the past and present and to make the Chattanooga Haunts program relevant and exciting to its youth.

We began the PD as we begin the Haunts

curriculum, with a community walk and open dialogue to elicit what the participants already know about the area’s history. The conversation that began deepened over the course of three days as we moved through the curriculum, from game coding to research and back again.What do you see? Who is here? What are they doing? How do you feel in this space?

Prying the educators for possible “ghost stories” to explore in their game, I inquired about the naming of Martin Luther King Boulevard. Did King have a role in the civil rights movement here? The answer I got was not so simple.

“Remember the I Have A Dream Speech? There’s a reason he says, ‘Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee…’ Do you know why?”

According to this educator (and verified by our consequent research in the Times Free Press), Lookout Mountain was segregated during the time of King’s speech; home to black Chattanoogans and known for the adversity faced by its residents. Another educator remarked that now Lookout Mountain was known as a wealthy and white area of town. We began to ask if our students would be interested in this history, how this change happened, and could it be connected to recent reports that Chattanooga is ranked top ten for income inequality in American cities, and is home to the second fastest gentrifying neighborhood in the country.

Back in the library and filled with newfound questions, we continued to tour Chattanooga on Google Maps. An educator noted that, MLK Boulevard aside, many of the city’s street names did point to individuals of local significance. Avenue after avenue, there were the names of Chattanooga’s founding families; those who’d played a big role in building the original city and investing in the railroad and trade industries. Before long, we were looking through a private collection of books on these families. Excitement grew and we began to realize that these family surnames matched prominent figures in modern Chattanooga– from local politicians to leaders of the region’s foundations, nonprofits, and the city’s rising tech industry. The ghosts from the past were catching up to our present!

Youth educator plays a coding game to learn the building blocks of computer programming.

Youth educator plays a coding game to learn the building blocks of computer programming.

Ideas percolated as we discussed issues of housing and racial justice over lunch, and the Haunts games began to emerge. One participant wanted to make a game to encourage students to take the bus out of their own neighborhood, and be more comfortable navigating the opportunities the city had to offer them. Another game idea would take its player through the role of being a housing developer, to learn about the needs and desires of local residents. Yet another, explored the various stakeholders of the city, and asked the player to try and prioritize the needs of their constituency as a public service provider. Yet another game would take its player through experiences of racial discrimination and privilege as they navigated the city to examine what adversity still exists along racial lines today.

PD trainings let educators play, be students, explore the ideas most important to them, and draw upon all of their existing knowledge. As they went through the curriculum as participants, these educators didn’t have to curtail their game ideas to fit core curriculum or censor themselves to accommodate the knowledge level of a middle schooler. They were able to enjoy a creative process authentic to their own strengths and knowledge and uncovered some challenges and curious truths along the way. Now, they are equipped with the inspiration, creativity, and skills to translate their own experience for the students they know best, and to create a game that is not just student-interest driven, but community driven.

PD trainings let educators play, be students, explore the ideas most important to them, and draw upon all of their existing knowledge. As they went through the curriculum as participants, these educators didn’t have to curtail their game ideas to fit core curriculum or censor themselves to accommodate the knowledge level of a middle schooler. They were able to enjoy a creative process authentic to their own strengths and knowledge and uncovered some challenges and curious truths along the way. Now, they are equipped with the inspiration, creativity, and skills to translate their own experience for the students they know best, and to create a game that is not just student-interest driven, but community driven.

SMES School

July 24, 2017 3:22 amGood blog! I’d like to read more about this. Please share other blogs in the same context (if you have any) 🙂